We often hear that question. Some time ago, the news was spread that hardly anyone still needs or learns Braille today because there are audio books and voice output on computers and smartphones. It is also repeatedly stated that most blind people are not capable of reading and writing Braille at all.

What is true and what is wrong? Here we look at facts.

Only apparently the age structure of blind people is the same as that of sighted people. But that is not true. As almost everyone’s eyesight declines over the course of their lives and some people even become very poor, older people are often classified as severely visually impaired or blind. Some go blind due to an accident, macular degeneration or inflammation of the eyes. There are many causes of visual impairment. Most occur in the course of life and not at birth. Thus the age pyramid is turned upside down in blind people.

What does this have to do with literacy?

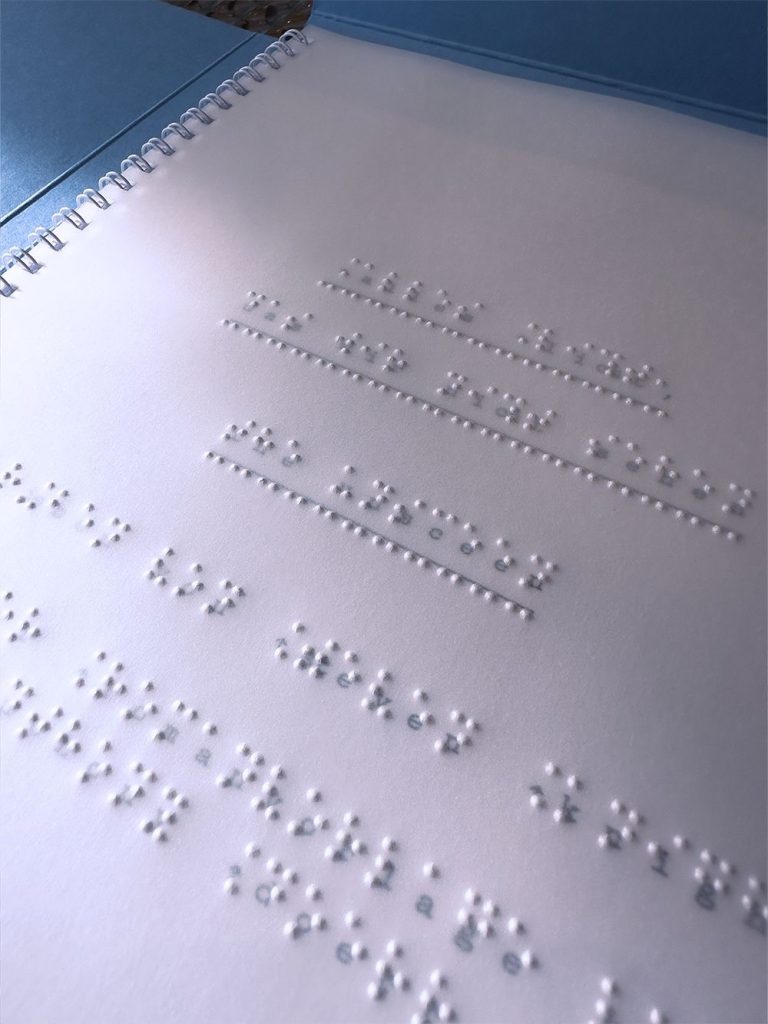

While every blind child goes to school and learns to read and write with Braille, this is of course not the case for older people. They do not go to school, but in the best case they do trainings. Everyone can learn Braille, but not everyone wants to. Some people don’t have the strength or motivation to learn Braille when they get older. That is regrettable but a fact. Older people do not find it so easy to learn and they have not developed the sensitivity in their fingers to keep the points apart. They have to acquire the sensitivity first. This is more difficult with increasing age. Most people who are over 50 years old and then go blind fall off the grid. So they become illiterate in old age. Here, large, palpably raised fonts help to highlight keywords. This is called profile writing or pyramid writing. However, reading them takes an extremely long time and is no alternative to Braille. However, it is the only form of readable font for this group. In the USA an experiment with fatal consequences was carried out when in the 90s it was believed that audio output on the computer was sufficient. Braille was not taught for years. A whole generation of blind Americans were thus deprived of their future. None of these people find a job on the regular job market as illiterates. Today, blind students are taught to read and write again at all schools. The children have a right to it like every seeing child.

Who can do Braille? How many are there?

All children who are born blind or blind in the first 16 years of life learn Braille reading and writing at school. After that, braille learning is optional, but almost everyone who goes blind under the age of 50 learns braille! Together these are about a third, that is roughly 50,000 people in Germany.

Is braille then worthwhile?

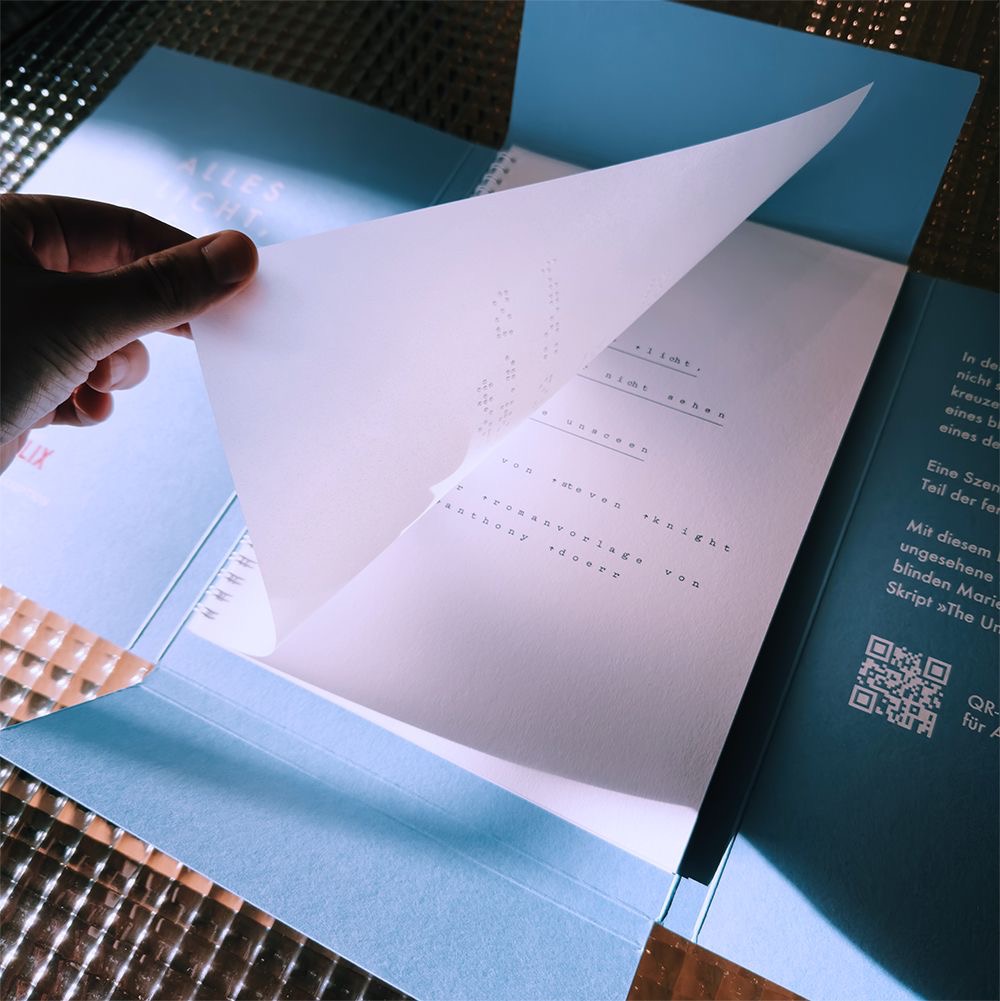

Definitely and without reservation, yes! Because a world without written information, without reading and writing leads inevitably to illiteracy and thus to absolute lack of opportunity on the job market and in the further training and complicates the participation in the social life completely substantially. For the group of blind people, not offering braille is often a lack of information and dependence on those who see by chance. Both are unacceptable for human rights and the individual. The question of the absolute number of beneficiaries is often asked in order to ask whether this can be justified financially. With the same argument one would have to question elevators, escalators, cycle paths, roads and the Internet in more remote areas and much more. Some of these would not have no alternative – Braille, on the other hand, does. „But I have never had a blind visitor here before“ is of course the result of the lacking or inadequate offer. Why should a blind person go to a museum where there is nothing for him except an overview map and an audio guide?

How to do the right thing?

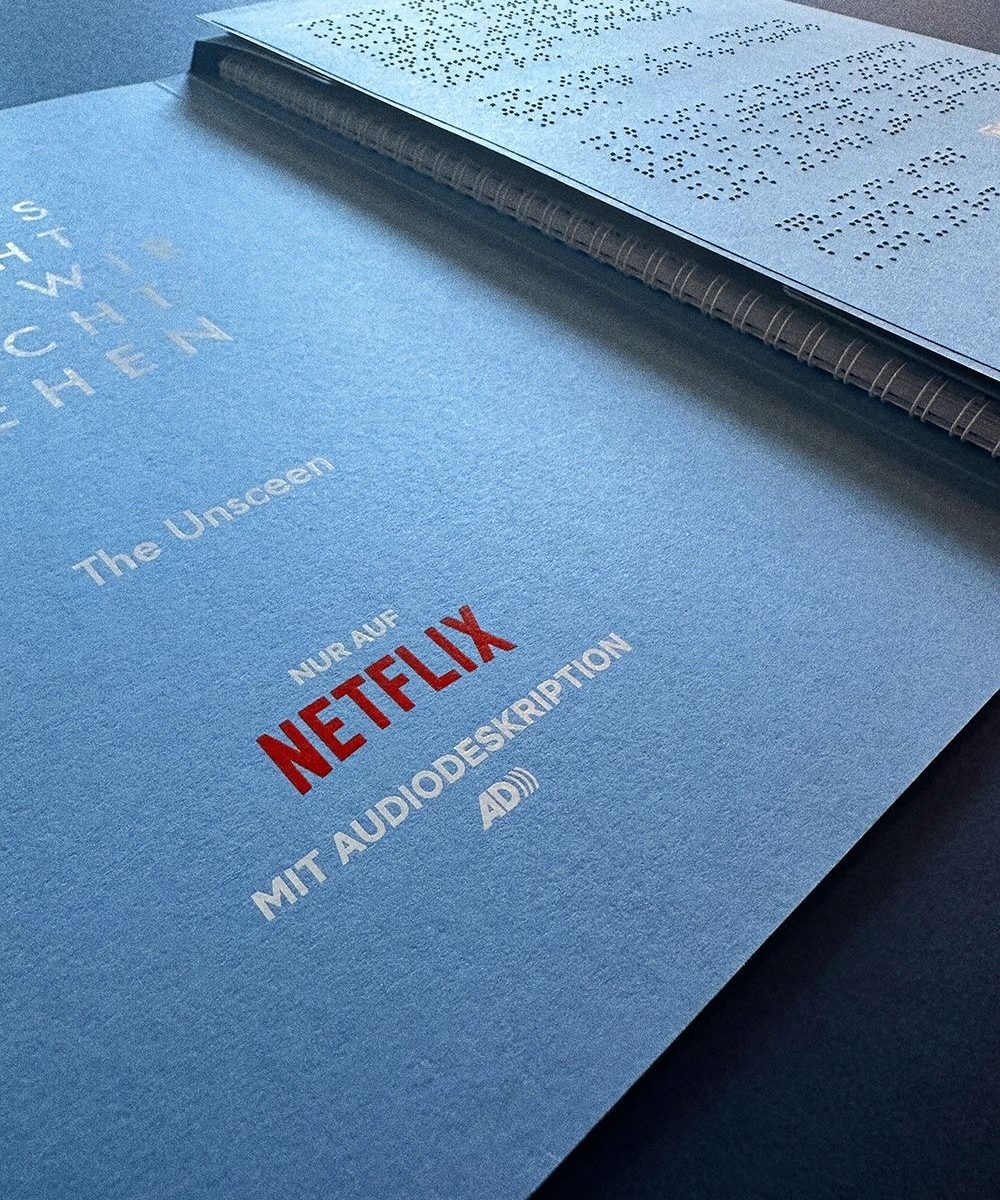

The prerequisite for the chance of participation is that information is actually provided in Braille. Everywhere and as much as possible. Compared to visual communication, however, it remains a fraction. This is the sign we have to set. This sign is a non-negotiable must if one speaks of an inclusive society. A society in which we also want to live when we are old or have temporary impairments, permanent disabilities ourselves or with relatives. We all want to continue to be able to make our contribution to working life and family life and not be excluded.

Understood. And where should Braille be used?

Wherever it makes it easier or even impossible to distinguish between products. Where the autonomy of a blind person is made possible by receiving information or being able to operate devices without being forced to ask someone (of course he is still free). Where education and knowledge transfer becomes possible. Where orientation is made easier.